Restoring trust in science and health? (part 1 of 2)

NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya on the replication crisis, academic freedom, and the "science" of the covid era

Further to this post…

I listened with interest to some of what Jay Bhattacharya — Professor Emeritus of Health Policy at Stanford University, and the new Director of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) — had to say in this recent long interview with US neuroscientist and podcaster Andrew Huberman:

The podcast is almost four-and-a-half hours long, and the discussion ranges widely:

Below are transcripts (with emphasis added) and comments on highlights from these sections:

…Early Career Scientists & Novel Ideas (01:21:43)

Incentives in Science… Replication Crisis (01:45:33)

Public Trust & Science, COVID Pandemic, Lockdowns, Masks (02:51:23)

A follow-up post will feature the sections:

Vaccines, COVID Vaccines, Benefits and Harms (03:36:03)

Do Vaccines Cause Autism? What Explains Rise in Autism (04:06:47)

“Early-career scientists are essentially doing the work of the older-career scientists”

[1:22:43]

For context, this is a rough outline of a typical scientific career in academia:

do a first degree

do a second degree — PhD or equivalent, sometimes called a doctorate (with someone working towards a PhD being a graduate student or postgraduate student)

do one or more “post-docs” — short for post-doctoral research

apply for independent research funding

climb the ladder towards being a full professor, via (in the US at least) assistant professor

[Bhattacharya] In the 1980s, the age at which scientists won their first large grant… was mid-30s… [but] young early career scientists take much longer now to be able to get support to test their ideas out than they did in the 1980s. This is important for innovation because it turns out… this is [a] paper that I published… that it’s early, curious scientists that are most likely to try out new ideas… in their published work…

Here is the paper:

[Bhattacharya] …this is depressing… for me… a man with grey hair but… the first year after your PhD is when you’re most likely to have newer ideas in your papers. And then every year after that, for every single year of chronological age, the age of the ideas you tend to work on tends to increase by about a year…

Right now, what we do is we take the careers of young scientists and effectively put them at the service of older… more-established scientists, so that the early-career scientists are essentially doing the work of the older-career scientists. So you have to have [one or more postdoctoral roles] before you have any chance of getting an Assistant Professor job where you could get test your own ideas out. Essentially the labor of young scientists is devoted to the ideas of older scientists in the current system… That wasn’t always true, and the NIH has played a role in that… and it’s part of the reason why we have had… more incremental progress than I would have hoped for…

“A lot of… the things that we think we know… even with some fair degree of certainty are probably not true”

[1:46:29]

[Bhattacharya] Science is a collaborative process but the incentives within science for individual advance can often lead to a… structure that elevates careers without necessarily producing truth…

[Huberman] Very tactfully put…

[Bhattacharya] There’s a colleague of ours at Stanford named John Ioannidis… absolutely brilliant scientist… [among] the most highly cited… living [scientists] in the world. He wrote a paper in 2005 with a title [something like] Why Most Published Biomedical Papers Are False…

A brief profile of Ioannidis can be found here in the post mentioned at the top of this article.

Here is the Ioannidis paper to which Bhattacharya refers, the title actually being Why Most Published Research Findings Are False:

Ioannidis’ summary — NB this was published in 2005:

There is increasing concern that most current published research findings are false. The probability that a research claim is true may depend on study power and bias, the number of other studies on the same question, and, importantly, the ratio of true to no relationships among the relationships probed in each scientific field. In this framework, a research finding is less likely to be true when the studies conducted in a field are smaller; when effect sizes are smaller; when there is a greater number and lesser preselection of tested relationships; where there is greater flexibility in designs, definitions, outcomes, and analytical modes; when there is greater financial and other interest and prejudice; and when more teams are involved in a scientific field in chase of statistical significance. Simulations show that for most study designs and settings, it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias. In this essay, I discuss the implications of these problems for the conduct and interpretation of research.

Back to the interview…

[Bhattacharya] When you make a title like that for a scientific paper, it had better be convincing. And in just a few pages it’s an utterly convincing paper. And [the reason why most published research findings are false is] not because scientists commit fraud. That’s not the reasoning behind it. [It’s] because science is hard… You publish a result you believe it to be true… you have some statistically significant result at some level… [but for] some percentage of the time, even though you believe the result is true…

It’s been peer-reviewed… by your colleagues… [But] the peer review actually doesn’t involve… the peer reviewers taking your data and re-running your experiments… They just read [past tense] your paper, looked for logical flaws, didn’t find any and then they recommended [to] the editor [that your work] be published. So the peer review is not a guarantee that it’s true.

I am reminded of Prof Norman Fenton, featured in this post…

…who stated recently, and with good reason, that:

The entire process of academic peer review has become so corrupted and disfunctional [sic] that it is almost meaningless. And, as our own experience with The Lancet indicates, that the more ‘prestigious’ the journals the less the value of what they publish.

And this article from Maryanne Demasi, PhD:

Problems that have plagued medical journals for decades include the failure of peer review, replication crisis, ghost-writing, and the influence of Big Pharma.

In 2004, Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet wrote, “Journals have devolved into information laundering operations for the pharmaceutical industry.”

More recently, Peter Gøtzsche, one of the founding fathers of the Cochrane Collaboration said, “The medical publishing system is broken. It doesn’t ensure that solid research which goes against financial interests can get published without any major obstacles.”

Back to Bhattacharya…

[Bhattacharya] [And while] you have some statistical significance… that your data meet [certain criteria]… even with that, some percentage of the time the published result is going to be false. [And] if you think of science a priori is hard, any result that you publish is most likely going to be a false positive result.

[Huberman] The so-called negative results aren’t incentivized. [It’s] very hard to get a good paper published for showing that something isn’t true. It happens… But no self-respecting graduate student or post-doc who values their life is going to say, “Hey, I want to go in and try and disprove the hypothesis of one of the more famous people in the field...” And no one shows up in graduate school and says… “I love these papers. Let’s replicate them…”

[Bhattacharya] The published biomedical literature… something that I’ve searched basically every day for… the last 40 years… most of the time… in that literature, the papers I’m reading, even though they say… their result is true… [it] is likely not true… I had a professor in medical school [who] once told me… “Look, half of what we’re teaching you is false.”

[Huberman] I’m glad you’re pointing this out… [I know of] a very prominent neurosurgeon, perhaps one of the most prominent neurosurgeons in the world… [who was asked], “What percentage of information in medical school textbooks do you think is false?” And he said, “Half.”

And then the second question was “What do you think the implication is for people for human health?” And he said “Incalculable.”

[Bhattacharya] Exactly. And that’s true of the biomedical literature as well… The published peer-reviewed biomedical literature is not reliable… [That] is the bottom line. A lot of… the things that we think we know… even with some fair degree of certainty… are probably not true. And… the question is… “Which half?” We don’t know the answer to that question…

And this is done even with pure goodwill and no fraud at all. And the reason is a combination of the fact that science is hard and the incentives we created for publication… Those two together mean that… the biomedical scientific literature is not reliable.

I’ve talked with drug developers who tell me that… before they make vast investments in a Phase III randomized trial or… even Phase I or Phase II… studies… they conduct independent replication efforts of the basic biomedical literature to see if it actually is true. Now those are private replication efforts so that the drug developers know which parts of the literature are true and false, but… the scientific community at large doesn’t know.

We’ve set up a system of publication that guarantees that much of what we think is true is not true. That’s a major problem for science. And it’s linked to this idea that you have to publish or you’re out. It’s linked to this idea that if you… publish failure you’re out. It’s linked to… [the] reward that we give to scientific volume… like the number of papers we publish and scientific influence…

[A brief discussion of the so-called h-index citation metrics including the observation that Watson and Crick’s famous paper on DNA wasn’t peer-reviewed]

…we reward scientists with the volume of papers they publish. What we don't reward scientists for is honesty about their failures. We don’t reward scientists for pro-social behaviour… where you collaborate… share your data openly and honestly. In fact, we punish scientists for that…

Right now, if somebody comes to me and says, “Jay, I want to replicate your work...” (I’ve trained myself not to think this way, but it’s really hard not to, given the structure we’re in…) I’m going to think of that as a threat. What if they don’t find what I found… I’m a failure, right? The failure to replicate is seen as a failure of the scientist rather than the fact that science is hard and that it is difficult to like get results that are true, even with the best of will. And we punish scientists for that.

We essentially reward scientists for… a set of things that creates incentives for the replication crisis to happen. So the solution to the replication crisis is to address those things… measure the pro-social things that scientists could do… recreate the incentives away from simply influence and volume. I’m not saying you shouldn’t reward influence and volume. I’m saying you should reward a fuller set of things…

“My academic freedom was pretty directly attacked… Stanford failed the academic freedom test”

[2:49:35]

This next section features discussion of the covid era.

[Huberman] I’d like to pivot slightly to some issues related directly to public health. We have a kind of fork in the road here as to whether or not we focus on issues of public health from the recent past for which you became best known… covid and the lockdowns, or whether or not we focus on public health issues that are are more relevant now.

I was told by many many people who are not scientists but care a lot about science that “until the scientific community acknowledges two things, they don’t want to give another dollar to science. Those two things are [firstly] the replication crisis… we talked about this… and, by the way, I think your plans to deal with that are fantastic. I love this idea, and I think many students and post-docs will be excited to be part of the correction process…

[Secondly] an admittance of error in our past. I want to be very clear, not to protect myself (I have plenty of work to do no matter what) [that] these are not my words… The words were: “The scientific community did us wrong. The lockdowns were unfair to, in particular, working-class populations. We were told one thing about masks then told another. We got a kind of loop-the-loop of foggy-speak politico messaging about vaccines and what they did do or wouldn’t do.”

And basically I hear from a lot of the general population — not just people on the MAGA, MAHA…whatever-you-want-to-call-it side, but also a lot of… people [who] are truly in the center… that they lost trust in science and scientists, and they will not consider restoring that trust until scientists admit that they made some mistakes.

And it took me a while to hear that message, because I’m like “Hey, listen… I have friends trying to cure blindness, cure Alzheimer’s, use a brain-machine interface to cure epilepsy, and get paralyzed people to walk. And you’re talking to me about something that happened [years ago now]… But I finally had to just stop and listen… because they kept saying, “We don’t care.”

It’s almost like big segments of the public feel like they caught us in something… as scientists, and we won’t admit it. And they’re not just pissed off. They’re kind of like done. I hear it all the time. And again, this isn’t the health-and-wellness, supplement-taking… anti-woke crowd. This is a big segment of the population that is like, “I don’t want to hear about it. I don’t care if labs get funded. I want to know why we were lied to or [why] the scientific community can’t admit fault.

And I just want to land that message for them, because in part I’m here for them, and [to] get your thoughts on… what you think about… let’s start with lockdowns masks and vaccines, just to keep it easy. And what do you think the scientific community needs to say in the light of those [things] to restore trust…

[Bhattacharya] …I was a very vocal advocate against the lockdowns, against the mask mandates, against the vaccine mandates, and against the sort of anti-scientific bent of public health throughout the pandemic. I’ve also argued that the scientific institutions of this country should should come clean about our involvement in very dangerous research that potentially caused the pandemic…

[Huberman] The so-called lab hypothesis…

[Bhattacharya] Yes… let’s just stay focused on on lockdowns. I want to make the scientific case that they were a tremendous mistake and that that was known at the time… Let me just focus on one aspect of it… the school closures…

What the public at large now sees is that American kids, especially minority kids, are two years or more behind in their schooling. We decided during the pandemic that children ought to learn to read — as five-year-olds or six-year-olds — remotely… in Zoom. We decided that in-person schooling didn’t matter anymore.

My kids in California were kept out of… school for a year and a half. If they saw the inside of a classroom, it was with plexiglass, separated from their friends… eating lunch isolated, alone. The message to American school kids was essentially: “Your school doesn’t matter. Your future doesn’t matter.” [And] American public health embraced that entirely.

In Sweden they didn’t close schools for kids under 16 at all… Anders Tegnell, the head of Swedish public health, explicitly made that a priority. [And] in the summer of 2020 the Finns and the Swedes compared their results. The Finns had closed schools in the spring of 2020, and the Swedes had not. And they found there was no difference in health outcomes for covid. The teachers… in the Swedish schools… they had no worse outcomes than other workers in the population.

And on the basis of that evidence, and the fact that we know that closing schools harms the future health and well-being of kids… even short interruption of school… we knew that for a fact based on a vast literature that existed before the pandemic… many schools around Europe opened up in the fall of 2020. The scientific evidence was abundant and clear even by late Spring 2020 that… the closure of schools… was a tremendous mistake.

And yet when I wrote the Great Barington Declaration with Sunetra Gupta of Oxford University and Martin Kulldorff of Harvard University in October 2020, I faced vicious attacks by the scientific community and the medical community for being unscientific about school closures.

[Huberman] Were there threats to your job at Stanford?

[Bhattacharya] Yes.

[Huberman] Real threats or just people saying, “We’re going to take away your job”?

[Bhattacharya] In March 2021, I was part of a round table with Governor DeSantis [of Florida]… a policy roundtable where he asked me whether there was any evidence that masking children had any impact on the on the spread of the disease. And the answer is [that] there’s not a single randomized study that looked at kids. The US was an outlier in recommending that kids as young as two years old get masked. In Europe… 12 was the age. There were no studies.

In response to that, a hundred of my colleagues signed a secret petition… effectively asking the president of the university to silence me.

[Huberman] Were you contacted by the university administration?

[Bhattacharya] No, I found out about the petition from a couple of my friends who leaked it to me. And then I went to the press and said, “Look… you should go ask the president about this.” And… then… he had… this mealy-mouthed statement about academic freedom, but also essentially… that it’s really important that we obey public health authorities or something [like that]…

And in 2020 I’d been subject to all kinds of sort of attacks on me… I’ll just say that Stanford failed the academic freedom test. It didn’t hold a scientific conference on covid with alternative viewpoints… that were anti-lockdown until 2024 when I organized it… even though I asked to have a conference in 2021 and 2022.

[Huberman] But your job security wasn’t threatened in a direct sense… No-one came along and said, “Hey… quieten down or else you’re going to lose your job.” So in that sense you had academic freedom from the top?

[Bhattacharya] That’s not true. I was asked to stop going on the press in 2020… by the… dean of the medical school. My academic freedom was pretty directly threatened... I wrote and published a study on measuring antibodies in the population… a study that… was replicated dozens of times… around the world. And I was essentially ordered to redo that study. They interfered even before I had… sent the paper in for publication. When I say “they” I mean the administration of the medical school… My academic freedom was pretty directly attacked, and I wrote a piece [about] how Stanford failed the academic freedom test. You can go read about [it]…

Here is the article, from January 2023:

And here are last two paragraphs:

Academic freedom at Stanford is clearly dying. It cannot survive if the administration fails to create an environment where good-faith discussions can occur outside of a framework of ideological rigidity and the false certainties that ideologues — and governments — wish to impose on us. Stanford missed the opportunity to sponsor COVID policy forums and it deplatformed dissenting voices. Several prominent faculty exploited this environment, engaging in actions that directly violated basic academic norms.

A precedent has now been established. Faculty at Stanford should rightly worry whether their professional work will lead to deplatforming, excommunication, and political targeting. In this environment, professors and students alike would be wise to look over their shoulders at all times, in the knowledge that the university no longer has your back. And members of the public should understand that many of those urging them to “trust the science” on complicated matters of public concern are also those working to ensure that “the science” never turns up answers that they don’t like.

Back to the interview…

[Bhattacharya] There’s a sense of positive and negative academic freedom. A negative academic freedom means there’s no active attack on me and my capacity to do work. I think Stanford failed that as well. There was an active attack me.

For instance, there was a a poster campaign all around campus with my face on it, essentially accusing me of killing people in Florida for advising… Governor DeSantis that there was no evidence that masking children benefited anybody… and essentially [saying that I] was a threat…

At the same time, I was getting death threats from people… The former head of the NIH [Francis Collins] wrote an email to Tony Fauci four days after we wrote the Great Barrington Declaration… calling for a “devastating takedown” of the premises of of the declaration. That resulted in essentially press propaganda pieces… the New York Times and elsewhere… essentially mischaracterizing what the Great Barrington Declaration said, which was to protect older people better and… let kids go to school… essentially mischaracterizing in a propagandist way… saying we wanted to let the virus rip. And that led to death threats against me.

[And at the] same time there’s this poster campaign all around campus. I called the campus police. I told… the folks in the department, the medical school, that this was happening and… their response was to send me to a counselor to reduce my online presence.

So Stanford absolutely failed during the pandemic… Stanford should have had… debates in 2020. We had prominent faculty people like John Ioannidis and Scott Atlas and others… Michael Levitt[who shared the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry] who were opposed to the lockdowns and yet we couldn’t get a hearing…

“The idea that closing schools is good for you… that you wearing a cloth mask prevents you from getting covid… that immunity after covid recovery doesn’t exist… that the vaccine will protect you from getting and spreading covid forever... None of that was rooted in science”

[3:08:53]

[Bhattacharya] There’s two ethical norms in science and… they competed with each other… In science, free speech is an absolute must. If you have an idea that’s different from mine, you should be able to express it and then we can test each other’s ideas out. We can maybe devise an experiment to decide… and [based on] whatever the experiment says, we’ll say, “Okay, you’re right and I’m wrong”… That’s how science advances… through… this process of people talking to each other… having free speech… The ability to come up with ideas and and articulate them… defend them is absolutely fundamental to the progress of science.

Public health has a different ethical norm… of unanimity of messaging. [And] this ethical norm has as its moral basis that the communications that public health puts out are grounded in consensus science.

So, for instance, if I were, as a former professor… at Stanford [to] go out and… say smoking is good for you… well, I’ve committed an ethical sin. I’d have done something really deeply wrong, because the scientific basis for the idea that smoking is a terrible thing for you… really harms your health in concrete ways… that’s… rock solid in science. So the idea that I as a person who works in public health shouldn’t go out and say smoking is good for you… that has a good ethical basis rooted in science.

[But] the idea that closing schools is good for you… the idea that you wearing a cloth mask prevents you from getting covid… the idea that immunity after covid recovery doesn’t exist… the idea that the vaccine will protect you from getting and spreading covid forever... None of that was rooted in science. And yet the public health authorities of this country decided that they were going to enforce the same kind of… ethical constrictions on those topics as they do [with] smoking.

[Huberman] When you say none of it was rooted in science, are you saying the science was mixed, or there was literally no evidence?

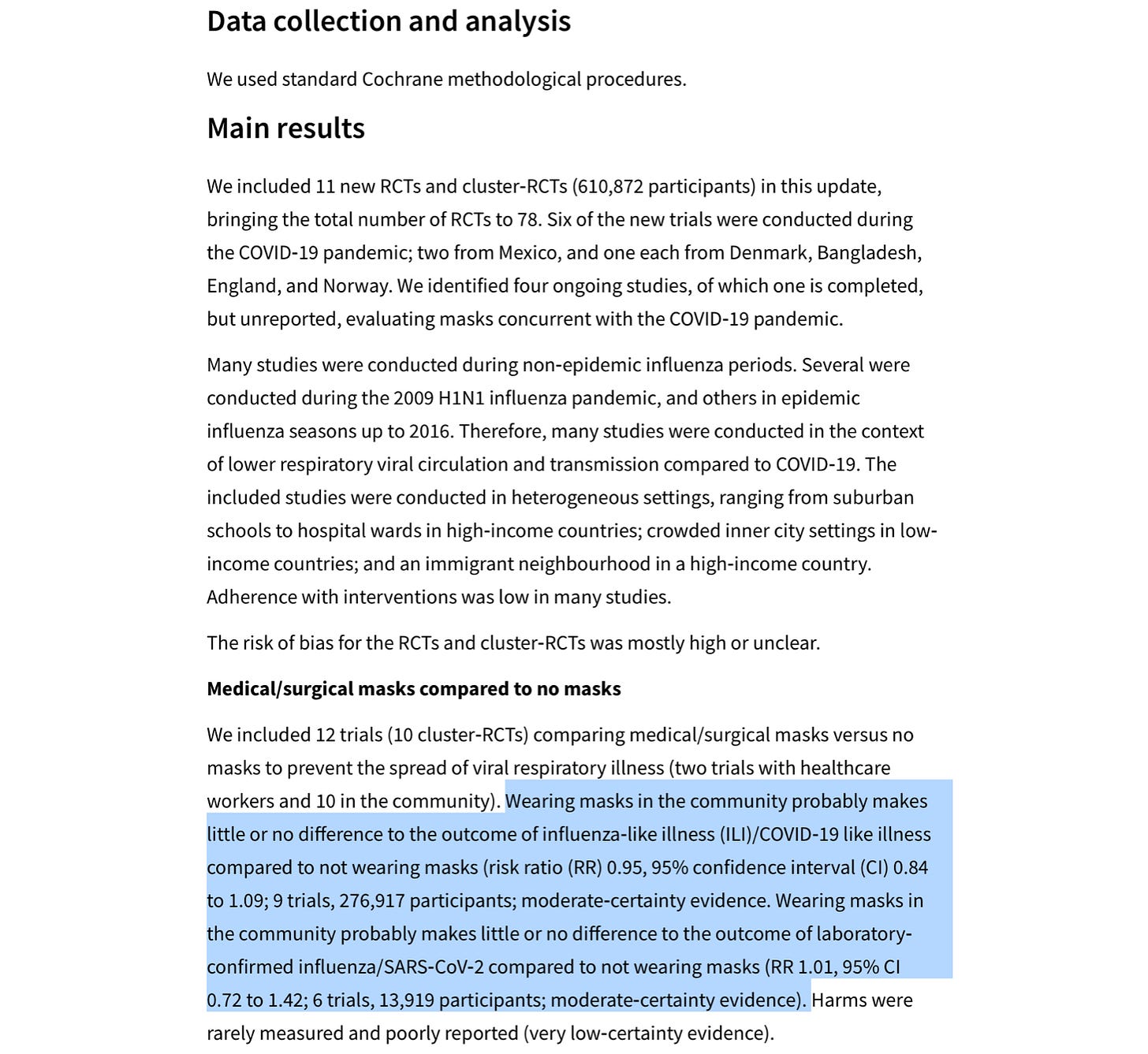

[Bhattacharya] There was really no science. So, for instance, the idea that cloth masks prevent you from getting and spreading respiratory diseases… There were a dozen randomized trials on flu before the pandemic, and… there was a Cochrane report looking at the literature on masking and influenza. And they concluded that the evidence was weak at best that these kinds of cloth masking in population settings actually prevent… the spread of influenza.

Here is a snapshot from the 2023 Cochrane review:

[Huberman] I heard a number of people say, “What’s the big deal about wearing a mask…? It’s not the same thing as a vaccine. It’s… a mask”… I’m just opening this up for sake of of consideration… Why did the masks become such an issue? Was it because it was a mandate? Is that what it’s really about?

[Bhattacharya] The mandate mattered, but… there were harms, some of which were recognized, some of which were not. For instance, I heard from parents of… hearing-impaired kids that the mask-wearing impaired the ability of the kids to learn to lip read…

I am reminded of this recent post…

…featuring this recent article from retired NHS Consultant Clinical Psychologist Dr Gary Sidley, in which he urges, in the context of masks:

Let’s not forget:

the swathes of babies and toddlers who failed to bond with their faceless care givers, thereby stunting their longer term cognitive and emotional development…

the many victims of historical physical and sexual abuse who were further traumatised by the mask requirements…

the 18 million UK adults with hearing difficulties who — because masks muffled voices and made it impossible to lipread — were plunged into a communication vacuum…

the patients with existing respiratory problems whose breathing difficulties were exacerbated, those who were put at greater risk of contracting pneumonia and other bacterial infections, and those who were exposed to the inhalation of micro-plastics…

the millions of distressed and frightened NHS service users and care home residents who, as a consequence of the often stymied relationships resulting from masked protagonists, experienced sub-optimal care…

the rational minority who, because they opted not to wear a mask, were harassed and abused by others. On one occasion such an assault led to the death of a young woman…

And Bhattacharya points out something else…

[Bhattacharya] …it’s also true that if you adopt and embrace public health messaging that’s self-evidently not rooted in science, you’re going to undermine the public trust in science and in public health.

[Huberman] I will say, based on these voices that I hear from a lot, that’s what they're asking for. They’re asking for the exact message that you’re delivering now, which is… I’ll say it differently… They want to hear the scientific community say, “We messed up.”

[Bhattacharya] And we should. We should absolutely say that… For instance, you wear a mask while you walk into the restaurant… you sit down to eat, and you take your mask off, and that protects you protects people from getting and spreading covid? How? Everyone could see that. You don’t need to be a scientist to see that. That was obviously ridiculous public health messaging…

[Bhattacharya] And let’s just say… you asked… could this public health messaging be dangerous. Well, yes. Imagine someone who’s… 80 years old… They have a lot of chronic conditions. It’s the height of the pandemic…

And they’re told, “If you wear a cloth mask you’re safe.” [Then] they go out in public and take risks that they otherwise would not have taken on the idea that they’re safe wearing a cloth mask and they get covid. The recommendation not rooted in science actually could end up killing people and probably did… so… none of these things are… low cost. It may be low cost to somebody who’s not particularly bothered by mask wearing, but [the policy] and still nevertheless [ends] up causing harm. And I think it… did.

I remember making a similar point about the false sense of security back in 2020.

These days, I wonder how much robust evidence there actually is that viruses spread from one person to another. And to what extent it is merely the case that the susceptible fall ill due to the inescapable presence of an airborne virus whose particles are much smaller than the holes in a mask, let alone the gaps around the side.

And then there is the issue of virus particles entering through the eyes…

But in any case, there is little doubt in my mind that the main purpose of introducing face coverings — at the height of summer — was to perpetuate fear in order to maximise the number of people willing to take covid injections.

After all, during Spring 2020, at the end of the annual respiratory virus season, they told us not to wear a mask…

Something changed, and it wasn’t based on science.

Update: part 2 is here:

Unexpected Turns homepage

The most-read articles can be found here