Assisted suicide: "This is not the Bill the public thought they were getting"

Recent mainstream media articles and evidence from the official Scottish Covid Inquiry for context, plus a summary from Danny Kruger MP

In the context of the forthcoming report stage and third reading of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill scheduled for Friday 16th May, I thought it worth sharing various recent mainstream media articles and evidence from the official Scottish Covid Inquiry, plus a summary from Danny Kruger MP.

“Some now believe the use of so-called ‘silence me’ drugs led to many avoidable deaths”

“Some people were forced into agreeing ‘Do not Resuscitate’ plans”

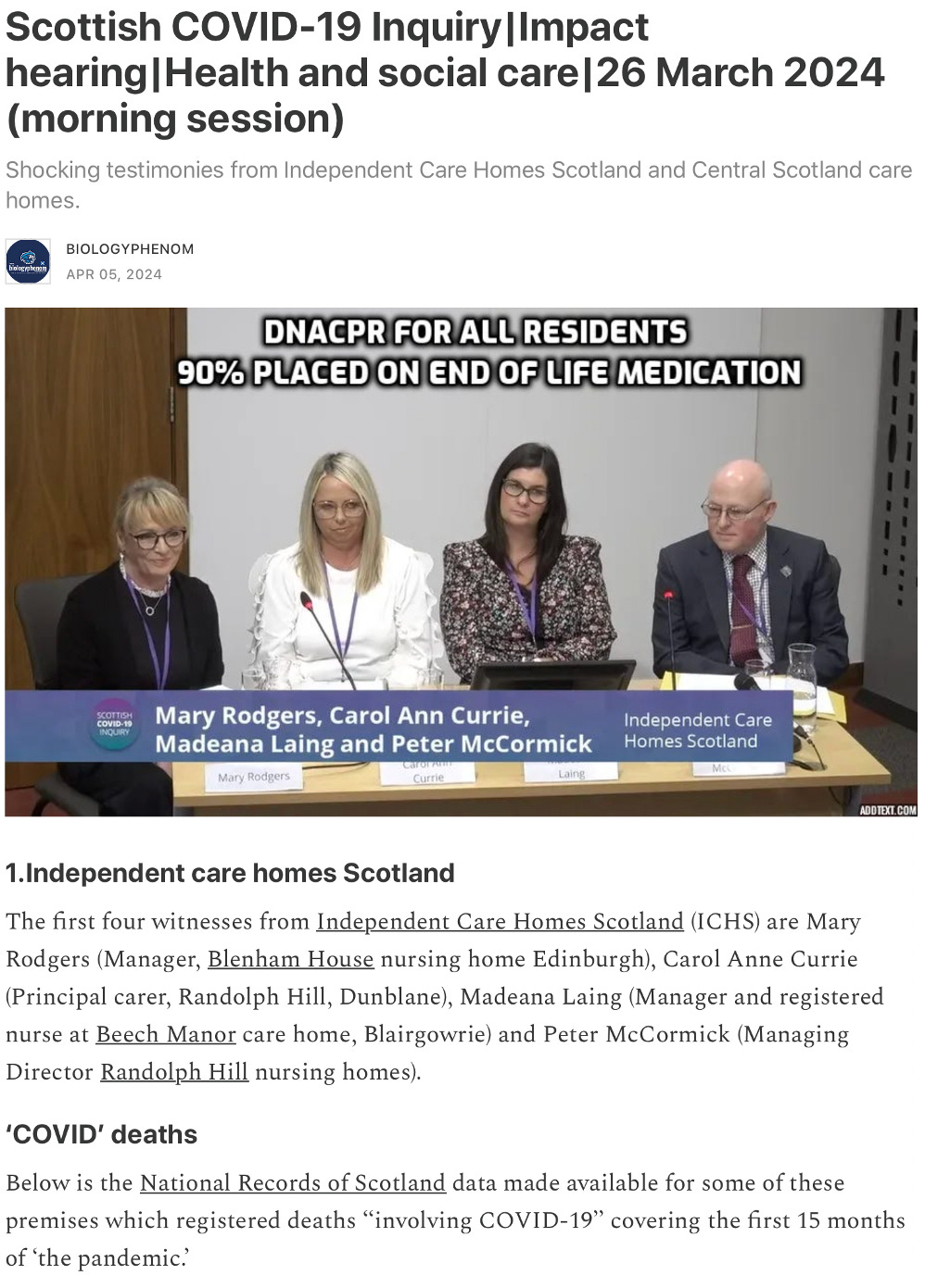

“DNACPR [Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation] for all residents… 90% placed on end of life medication”

“Disabled people were secretly given ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ orders… [they] felt like their lives were ‘not worth saving’”

“A ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ plan was put in place for a grandmother… against the family’s wishes”

“Whole care homes… blanket DNACPRs… they felt written off”

“Police Scotland look set to probe the allegedly fraudulent use of ‘Do Not Resuscitate’”

“Some suspect that their loved on was suffering from neglect, dehydration and starvation”

Link — where the video is embedded and can easily be viewed

“This is not the Bill the public thought they were getting”

Below is a summary from Danny Kruger MP, speaking in the House of Commons on 25th March (transcript below):

If we are to [pass this Bill], we should recognise that what we are proposing to legalise is not healthcare. Indeed, new clause 36 recognises the essential incompatibility between the service proposed here and healthcare as it is traditionally understood in our country and enshrined in the NHS Act.

More than that, the foundations of healthcare in the West are contravened by the Bill. The Hippocratic oath contains the promise:

“Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course.”

That is the oath that doctors take, and it has been the ethical basis of medical practice in the west for millennia. The Bill would be the final, official abandonment of that ethical tradition.

I implore the Committee to reflect on the essential principle that healthcare is the antidote to sickness, whereas this proposal for assisted suicide is the antidote to life. That is the treatment that the Bill proposes to legalise. It is entirely different from healthcare, in principle and in practice. It is therefore no surprise that so many of the professional bodies involved in healthcare regard this proposed treatment as incompatible with their professions. The BMA [British Medical Association] agrees that this should be a separate service.

I was struck by a BMJ [British Medical Journal] article that appeared last November, “Reframing assisted dying through the civil law: possibilities and challenges for the UK”, which was written by a group of palliative care professionals. It sets out how, if assisted dying is to be legalised in this country, it might best be organised and delivered. New clause 34 and all that flows from it would enable us to design a better assisted suicide service than the one that the Bill would give us.

The honourable Member for Spen Valley [Kim Leadbeater] this morning and the honourable Member for Sunderland Central [Lewis Atkinson] this afternoon asked how it should be done, if we are to do it. My honourable Friend the Member for Reigate [Rebecca Paul] offered some suggestions.1 I will build on what she said by saying how I think the Bill should have been framed — indeed, how I and others, through the amendments we have tabled, have tried to ensure it is framed.

We have tried to match the Bill to the campaign for assisted suicide. Understandably, there is considerable public support for people at the end of their life, who are at risk of suffering a terrible, agonising death and whom palliative care cannot help, to have the right to end their life a few days or weeks early. We can argue about how many people that is. I think the number of people whom palliative care could not help if we organised our palliative care system properly is infinitesimally small — almost non-existent. However, we disagree on that, so let us assume that there are some people who will fall into that category. The campaign for this Bill is the campaign for those people to have the right to an assisted death, but that is not what we have in the Bill. What we have is a right for anybody who in the opinion of two doctors might reasonably be expected to die within six months to request and receive lethal drugs, all paid for and assisted by the NHS. That is not what the campaign has been for.

Let me suggest how, if we are to be honest to the campaign, we should design this thing: not as healthcare, but as a compassionate suicide service for people facing physical agony at the very end of their life. As we tried to ensure at the beginning of our deliberations, eligibility would be for people fearing pain, not for those feeling a burden. There would be a proper capacity test, not the Mental Capacity Act 2005 test. There would be proper, meaningful safeguards against coercion. We would have doctors and a multidisciplinary team at the right stage of the process: right at the beginning, at the first assessment. We would have all the appropriate signposting and palliative care provision as an alternative to assisted suicide. We would then have a proper judicial process to decide whether to approve the application.

As for provision, from assessment through to the final act it should not be in the NHS. It should not be provided by any profit-making providers advertising their services and receiving money for every death that they assist, which is what we have probably got with the Bill. It should be provided by non-profit organisations, should be tightly regulated and should be funded not through NHS commissioning or by the patients, but by philanthropy.

The scale of all this is to be discovered, I guess, if we pursue the Bill. It has been suggested that the lower end of the expectation is about 6,000 deaths per year. On the calculations made by the experts in the paper I cited, it would need a budget of about £10 million a year to manage a 6,000-person caseload. That is in the ballpark of what the campaign groups promoting the Bill have been spending, so I do not think that there would be any difficulty in raising that sort of money if it is what people want. After all, hospices have to raise millions of pounds every year to fund their work. I do not see why assisted dying services should not be able, and required, to do the same thing.

There was a way to do this more consistently with the campaign for assisted suicide. For the avoidance of doubt, I would have opposed that too, because even that much more honest and tightly circumscribed service would profoundly alter our society — it would send the signal that some people are better off dead, and I think it would be wrong for our country — but at least it would be honest. It would be consistent with the campaign.

I will end with the observation that what I have just described is what I think the public think the Committee is doing: designing a service like that for the small number of people at the very end of their life who are facing a terrible physical death. That is not what we have done, it is not what the Committee has approved, it is not what the original Bill said and it is not what the Bill now says as we send it back to the House. I hope that the public and our colleagues in Parliament will recognise that this Bill is not the one that they thought they were getting.

For anyone wanting to contact their elected representatives in the UK, including MPs, this is a useful link:

Related:

And:

Unexpected Turns homepage

The most-read articles can be found here

Here is a short clip of Rebecca Paul MP speaking in another context about palliative care (transcript below):

We should be ashamed if this is where we end up as a result of this bill. How is this in any way recognising patient autonomy and giving them a real choice? It clearly isn’t. We will end up in a situation where patients take an assisted death because there is no other alternative for dying well. If as much effort was put into improving palliative care as has been put into legalising assisted dying, we would find ourselves in a situation with a much greater number of people being given the dignified, comfortable deaths they rightly deserve. It’s a travesty that we find ourselves considering the introduction of assisted dying while hospices are on their knees, and patients face a postcode lottery on receiving adequate end-of-life care.

![[SPCI-6] "I fear my father was euthanised, and I was told not to use that word at the Scottish Covid Inquiry. They did not like me using that word... They don't like the truth..."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!W4OK!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F15ef8fbb-0a2f-4f97-833f-6075f5f5b9c2_720x650.png)

![[SPCI-5] "I obtained his medical records... My brother had been placed on a trial... I found that his signature had been forged... that withheld the antibiotics"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0s22!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb5144d2d-d1e1-4195-af67-8aed4fd146aa_1450x1400.png)

![[SPCI-4]: "Even the organisations... that were meant to look after the interests of the elderly and the frail, they were useless… No-one spoke up for those without a voice, except their families"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fWnK!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdb3635cc-e1be-4fac-9cf5-6b71be58d94f_1154x1012.png)